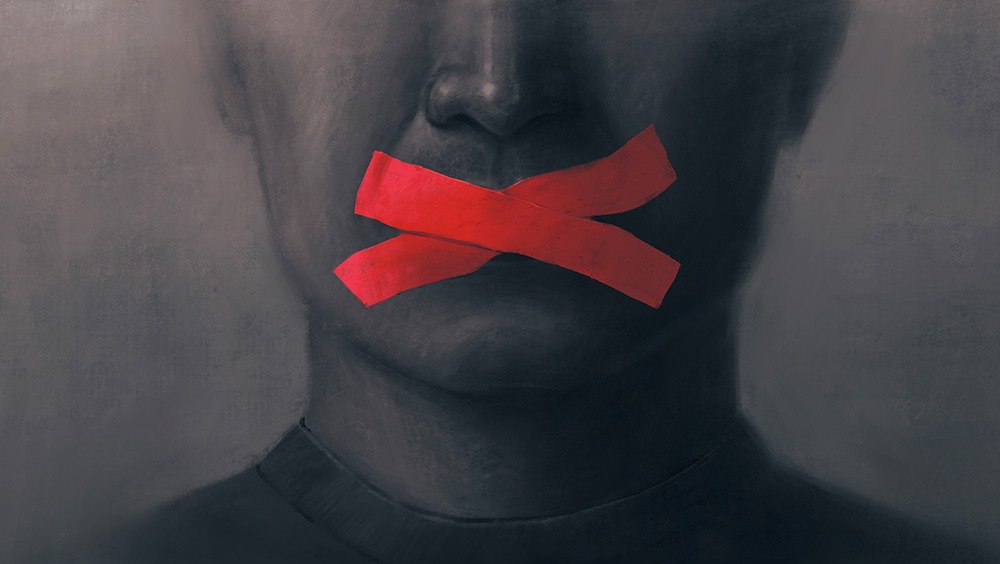

“I don’t think there’s been a time in my life where people were more openly afraid to express themselves.” Jimmy Hatch, a former Navy SEAL, reflects. “It breaks my heart.”

This remark is all the more striking coming from someone who has seen unimaginable violence in Iraq, Bosnia, and Afghanistan from more than 150 small-scale, offensive, and routine missions. Hatch’s perspective is haunting: The fear of speaking at home, he suggests, is beginning to mirror the sentiments seen in autocracies abroad.

The United States has a long history of violent behavior driven by political intent. Abraham Lincoln’s arbitrary suspension of habeas corpus during the Civil War, the January 6th insurrection, and countless assassinations of prominent political figures have all been embedded into the DNA of this country.

In response to political violence, the press has relentlessly covered, commented on, and critiqued political administrations for their wrongdoings. Upholding the journalistic principle of keeping officials in power accountable, the media is meant to remain independent of governmental control. Yet, as a resurgence of this violence takes root in the U.S., freedom of the press is under attack — both by state actors, donors, and journalists themselves.

Political violence has become a buzzword across news outlets, but what does it actually mean? Beverly Gage, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian at Yale University, defines political violence simply as “violence that has a political intent.” Political violence is not just about the act itself, but the threat behind the brutality and the signal to the populace that follows.

The assassination of conservative activist Charlie Kirk on September 10 at Utah Valley University is one of the most high-profile, mass-mediated examples. But political violence has long structured the lives of marginalized communities; Black Americans, in particular, have lived under a persistent presence of violence designed to maintain political order. From Ku Klux Klan terror during Reconstruction to the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Medgar Evers during the Civil Rights Movement, today’s headlines of lawmakers and political actors being assassinated are a continuation, not an anomaly.

Charlie Kirk was not attacked as a private individual, but as a political actor. It was a deliberate targeting meant to punish a viewpoint and warn others who share it. The signal from Kirk’s assassination becomes clear: fear and intimidation now suffocate the public sphere, making free speech feel physically dangerous. This, Gage warns, is the true corrosive effect of political violence: “At moments of pressure,” she observes, “people go very quiet.”

That quiet, she explains, is the product of what scholars call “the chilling effect” — a shared, often unspoken understanding that certain words carry consequences not only for one’s career, but potentially for one’s safety. Its power does not stem from overt state crackdowns or legal bans on speech. Instead, it emerges more indirectly and insidiously: through the constant threat of political retribution. Silence, in this context, is not chosen; it is coerced.

This chilling effect does not exist in a vacuum; rather, it is deeply intertwined with broader societal polarization. Graeme Wood, a lecturer in Yale’s Political Science department and a staff writer at The Atlantic, observes that polarization isn’t inherently bad. “What’s bad is polarization in isolation from the other pole,” Wood states.

Division becomes dangerous not because people disagree, but because they no longer engage with disagreement. Instead of confronting opposing claims, they caricature them. In such an environment, retribution becomes not only easier and tolerated, but rationalized. Why debate an opponent when you can delegitimize, and even dehumanize, them? Once your opponent is no longer seen as legitimate, silencing them feels less like censorship and more like restorative justice.

The tactic of delegitimizing opponents reflects a deeper problem. Hatch argues that political debate in the United States has been overtaken by a destructive fervor. “The new religion is politics. We’ve become a lot more secular, and politics has given us this fervor, the passion that religion used to,” he said. The lengths to which individuals go to defend their opinions have shifted from civic duty to existential struggle. They perceive the threat not only to themselves, but also to the larger community with which they identify through shared ideological beliefs.

Social media has facilitated the proliferation of identity-based communities like this. One of the clearest examples is the modern manosphere — a network of creators online that unite over male grievance, blaming feminism and social progress for the issues men are currently facing. The shared victimhood has become ingrained in one’s identity, seeing struggles with dating and job acquisition as a form of political betrayal. What begins as alienation shifts into mobilization, as young men come to see themselves not just as members of a community, but as players in a larger campaign to reclaim power. This movement then manifests itself into ideological tribalism.

Hatch warns that this ideological tribalism becomes particularly dangerous when leadership engages in retribution against opposition. Having witnessed societal collapse firsthand during his deployments abroad, he sees a familiar pattern: rhetoric that demonizes opponents and fosters isolation fractures social cohesion. “If we can learn to see one another’s humanity, our own humanity, in one another, that will help. But the rhetoric [that political leaders] use is such that we’re moving away from that type of thinking as a culture, as a society.” Hatch says. “And I think that’s dangerous.”

“Bosnia is a great example. Everybody circled around their little tribe…the Muslims, the Serbs, the Croats, [and] they just started killing each other,” Hatch describes. While Bosnia and the U.S. have apparent differences — one a fragile post-communist state shattered by ethnic nationalism and civil war, the other a long-standing democracy with robust institutions — Hatch reveals that the same emotional mechanisms exist. People stopped recognizing the opposition as humans with opinions, but merely as political agents with destructive values.

When President Trump, speaking at Charlie Kirk’s memorial, declared that he “hates his opponents” and does not “wish them the best,” he gave permission for ordinary citizens to see political rivals not as fellow Americans, but as non-human threats. Once leaders normalize punishment against opponents, citizens gravitate towards political extremes and fortify their beliefs. Public discourse halts, intolerance rises, and political retribution becomes attempted ideological purification.

As Anne Quaranto, a philosophy lecturer at Yale who studies propaganda and democracy, emphasizes, free expression is not just the right to speak — it also relies on the willingness of others to listen. Speech is a relationship, she explains, and when tribalism creates intolerant echo-chambers, the effects of political retribution extend beyond isolated acts of hostility: they amplify fear and make meaningful dialogue nearly impossible.

The chilling effect is not confined to just one country –– it has become a global phenomenon. In light of its pervasiveness, it is crucial to distinguish between censorship and retribution. Conflating the two risks harmful hyperbolic behavior, where exaggeration primes numbness and dulls public sensitivity.

Investigative journalist Matthew Cole of The Intercept draws a clear distinction between censorship and political retribution when he compares the experiences of reporters abroad with those in the United States. Outside of the U.S., journalists often face direct violence simply for telling the truth. In 2024 alone, the Committee to Protect Journalists reported at least 124 journalists and media workers killed. In warzones and autocracies, Cole recalls, “the Taliban were willing to kidnap journalists” to prevent critical reporting. These preemptive efforts to suppress information are not retribution. They are censorship in its purest form.

In contrast, the U.S. presents a subtler, yet still inimical, form of pressure. Cole cites the example of late-night host Jimmy Kimmel briefly disappearing from the air after commenting on Charlie Kirk’s assassination. “It wasn’t censorship,” he clarifies. “It was retribution.” Professional consequences like losing access to advertisers or platforms may not block speech directly, but they make speaking costly.

Cole recalls when the Trump administration restriction of the Associated Press’s credentials for access to the White House briefing room after the outlet declined to use the preferred term “Gulf of America.” According to Cole, this action from the Trump administration was “small and mostly symbolic” due to its limited ability to prevent reporting on the White House. Still, he does express his concerns about the broader implications of these acts of retribution.

“I am worried about newspapers, magazines, and prints because of the self-censorship,” Cole says. Over time, repeated retribution can push journalists into self-censorship, narrowing the scope of public debate. This raises the unsettling question: Is quiet coercion becoming the 21st-century strategy for controlling political information?

Structural factors in U.S. media amplify this dynamic. Broadcast networks, for instance, operate under licensing and regulatory constraints, meaning risky reporting could jeopardize their ability to air. “It’s a legitimate concern,” Cole notes, forcing preemptive caution. Editors and reporters may avoid controversial topics, sanitizing coverage to minimize perceived risk. Following Kirk’s assassination, he observed newsrooms “bending to not offend,” consciously narrowing coverage of inflammatory rhetoric to avoid becoming targets of retribution.

By connecting domestic patterns to global examples, Cole highlights a continuum of threats to free expression, from direct violence abroad to symbolic retribution and, ultimately, self-censorship. While the First Amendment of the Constitution prevents outright censorship, normalized retribution can quietly chill discourse, establish ideological extremes, and create conditions where formal censorship becomes more likely. Understanding the distinction between retribution and censorship, Cole suggests, is not merely semantic: it is essential to diagnosing the subtle pressures undermining democratic norms without unnecessarily amplifying fear.

Cole’s framework demonstrates that threats to free expression can escalate quietly, even in democracies with constitutional protections. Hatch situates this phenomenon within a larger global dynamic: the U.S. has, over decades, exported a culture of violence abroad, and the effects of that export are eventually seen back home.

“Look, Iraq’s gonna change America. America’s gonna change Iraq. You will learn the culture of death. And I think that we’ve kind of stepped into that, because that’s been our…export, really, hasn’t it?” Hatch states, reflecting the new, normalized reality of violence within the U.S. We’ve spent countless years trying to uphold the global standing of democracy and the protections of freedoms, but in doing so, have internalized that very violence we aimed to contain elsewhere.

Hatch’s observations about America’s familiarity with violence abroad highlight a broader truth: political violence leaves marks not just on the battlefield, but on the very fabric of domestic society. “We are the biggest weapons distributor in the world. I mean, those kind[s] of things have a recoil. When you shoot a gun, you shoot this projectile out of the end of the gun, but there’s an energy that comes back into you, and that’s the recoil,” he states.

Hatch emphasizes that the repercussions of exported violence are not abstract, but rather manifest as a kind of societal “recoil.” The familiarity with lethal force, the normalization of destruction, and the perception that violence can effect change all feed back into American society. “Our society, although very well protected, has become very accustomed to violence and not really having to pay the consequences. And that’s a pretty big problem,” Hatch notes.

The normalization of aggression, coupled with fear-driven silence, can shape how citizens engage with dissent and debate. This is not the first time the United States has faced such pressures, and it won’t be the last. These episodes, while frightening and disruptive, ultimately prompted reflection, reform, and the strengthening of civil liberties.

Gage recalls from her research on the Wall Street Bombing of 1920, that the “whole period in the late 19th and early 20th century, when acts of bombing and assassination and violent conflicts were incredibly prominent” that the same period “gave birth to the world of civil liberties and the ACLU in reaction to some of the crackdowns.” This pattern offers perspective on today’s climate of polarization and retribution.

Today, the pressure to stay silent in the U.S. comes from something far more obscure than overt legal repercussions. The imposed silence on citizens and journalists has already taken its course — several potential interviewees for this piece declined due to the inability of tying their name to a work that discusses retribution in light of Charlie Kirk’s assassination. Even among those who agreed to be interviewed, it was apparent that the pervasiveness of the “chilling effect” was collectively felt.

Despite the quiet, Jimmy Hatch reminds us that “you can’t kill an idea.” History shows that ideas endure when people resist the instinct to withdraw, choose dialogue over silence, and embrace shared humanity over demonization. In a time when political fear tempts many to retreat to a convenient stillness, the survival of democracy depends on our willingness to speak, listen, and challenge one another. Let your ideas flourish, and find a way to speak your truth.