All credit to Carlos Barrera, photojournalist from El Faro

In a small town in central El Salvador, thirty minutes from the capital, a young deportee says he can finally leave his motorcycle outside without fear—something unthinkable just a few years ago. He remembers when stepping out of his home meant living in constant worry, when gangs like Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) patrolled the streets and demanded loyalty or violence. When the gang tried to recruit him in 2022, during his senior year of high school, he fled to the United States to seek the safety his own country could not offer. Now, back home, he said the change feels surreal, “The gangs are gone in this neighbourhood, just gone.”

In another town not far away, Maribel Amaya, still waits for her 18-year-old son Jorge, who never came back from school—one of many detentions now familiar to families across El Salvador amid the country’s sweeping security crackdowns since early 2022. Jorge was wearing his school uniform when the police stopped him on his walk home from school in May 2022. Since then, she has carried folders of papers from court hearing after court hearing—letters from teachers, proof of grades—each stamped and ignored. In January this year, a court once again denied his release, offering no explanation. Jorge will remain imprisoned until 2026.

In Ilopango, an hour from the capital, Alexander Guzmán, a high school teacher and owner of a small taxi business, was arrested on the morning of March 27, 2022. He had been meeting his drivers for their weekly breakfast when police arrived. Both Guzmán and one of his drivers, Marco Tulio, were detained on charges of illicit association. After three days crammed “like sardines” in a local jail, they were transferred to Izalco Prison.

At Izalco, guards ordered the prisoners to strip, forced them to squat in the sun, and beat them as they ran between two lines of truncheons. Guzmán recalled the guards’ taunts: “You have come to hell.”

Tulio was beaten so severely that he bled out internally. He died just two months later. Guzmán’s cell—split between MS-13, Barrio 18, and civilians like himself—had no running water, no toilet paper, and no space to lie down. When prisoners prayed or sang, guards answered with tear gas. “Torture happened every day,” Guzmán said.

He kept track of the dead: 25 in Izalco alone, and 10 more in his sector in Quetzaltepeque. Some died from beatings, others from disease. Six months later, despite losing more than a hundred pounds, Guzmán walked out alive, making him one of the lucky ones.

This present situation can be traced back to the civil war that began in 1979, when the country first entered the cycle of violence and state power that shapes it today.

***

The civil war did not end until 1992, eventually leaving over 75,000 and deeply fragmenting the nation’s social and political livelihood. The Peace Accords offered a hopeful democratic transition, especially through the development of democratic institutions, but they failed to address the roots of the conflict: widespread poverty, limited education, inadequate healthcare, and mass unemployment. New institutions absorbed old habits, including the police force, composed primarily of former military officers.

In the postwar era, the Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA)—the right-wing party that dominated politics until 2009—entrenched economic divides, while the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN)—the former guerilla movement turned left-wing party—struggled to deliver social reform amid political polarization and the rise of gangs. What was meant to be a democratic reset slowly moved towards disillusionment with the parties, rising insecurity, and crumbling institutions.

Canadian researcher Doctor Tommie Sue Montgomery, a long-time analyst of El Salvador, noted that the gangs that would come to define everyday life in El Salvador did not originate there. Montgomery described how in the 1990s, thousands of young male deportees with ties to Los Angeles-based MS-13 and Barrio 18 arrived in El Salvador. With no support from the U.S., El Salvador was unprepared to absorb them. The gangs organized quickly, controlling neighbourhoods, extorting businesses, and enforcing their own borders. “By 2010, they controlled the vast majority of the country… as reflected in the number of homicides,” Dr Montgomery said. The gangs began to fill the power vacuum neither ARENA or FMLN were able to contain.

By the late 2010s, El Salvador had reached a breaking point. “The gangs were running at least 90% of the country on a daily basis,” Doctor Montgomery said. MS-13 and Barrio 18 controlled nearly every aspect of life for most working-class communities. The gangs were extorting families, recruiting teenagers, and enforcing invisible borders through brutal violence. Homicide rates were among the highest in the world. After decades of disillusionment under ARENA and FMLN, trust in institutions collapsed; fear became the rule of law.

***

In her 46 years documenting El Salvador, Doctor Montgomery has seen the country transform through civil war, political turmoil, and gang violence. Recently, she has spoken to hundreds of voices along both sides of President Nayib Bukele’s new order, from communities freed from gang extortion to families torn apart by the régimen de excepción, the state of exception that grants the government extraordinary powers including detention without cause and pre-trial incarceration. The stories above are drawn from her interviews, which chronicle a nation that feels safer than ever yet more wounded than it dares to admit.

Yet since 2022, people are starting to disappear again.

In Montgomery’s reports lie a man who has never seen a judge, a woman who gave birth in her cell, and families who still do not know where their relatives are held. These individual stories are not isolated, they sit within a much larger pattern of abuses that journalists have begun to uncover. “The documentation [by journalists] is now so thorough and so extensive,” she added.

Systemic abuse, erosion of due process, and the violation of human rights under the Bukele administration stand in stark contrast to the polished image of El Salvador that it aims to project overseas.

The photojournalist Carlos Barrera, who has covered the régimen de excepción for El Salvador’s only remaining independent investigative publication, El Faro, echoed this contradiction. “Poor neighbourhoods no longer live under the fear of gang violence… That space has been taken over by another kind of violence: violence exercised by the state,” he said.

Photographing the régimen de excepción since its earliest days, Barrera often is reminded of a quote by Russian writer Fyodor Dostoevsky: “The degree of civilization in a society can be judged by entering its prisons.” Barrera added, “That may be one of many conclusions to draw when observing what is happening in El Salvador today.”

The scenes Barrera documents are inseparable from the political figure who engineered the systems they originate from, President Nayib Bukele.

The only leader with fresh ideas and momentum in a political landscape eroded by ARENA and FMLN, Bukele seemed like the solution. His platform promised modernization, employment, and investment, which he sold through tweets, livestreams, and an intentionally approachable persona. Behind this image, he built what Doctor Montgomery labelled as a “social media ministry,” hiring young people to promote his image online and “disparage his opposition.” “They often played fast and loose with the truth,” she added.

Bukele’s Bitcoin experiment, making Bitcoin legal tender and stockpiling it in the national reserves, garnered international attention, and his bold ideas evoked a concrete move forward towards social and political reform in the minds of Salvadorans. His gang policies were successful, systematically dismantling the leadership of MS-13 and Barrio 18, drastically reducing violent crime in the country. After decades of institutional inertia, Bukele seemed beyond the old political binary: a leader who could finally change the nation.

***

Yet the authoritarian turn came quickly. Months into his presidency, supported by soldiers and police, Bukele stormed the legislative assembly to demand support for his budget that they refused to pass. His online machinery—amplified with troll networks, doctored narratives, and harassment campaigns—helped cement his victory and win his party a supermajority in the 2021 elections. The institutions that once constrained presidential power collapsed overnight, with the Supreme Court and Attorney-General first to go.

Reflecting on the contrast between Bukele’s pre-election promises and post-election actions, Doctor Montgomery offered two words: “He lied.”

For many Salvadorans, this concentration of power felt like a necessary evil. Ana Perez, a Salvadoran student studying abroad (The Politic agreed to use a pseudonym for her safety), said Bukele’s dominance has erased any meaningful opposition. “We’re on the road to authoritarianism,” she said. “Any political rival he may have, he’ll attack it. Any potential threat to his throne, he’ll attack it before it can grow.”

She understands why many ignore this shift. “If you’re living in poverty, extreme poverty, and you lived through the gangs, what is democracy to you?” she asked. “It’s not that people don’t understand, it’s that they don’t care.”

As Perez put it, Bukele had become Hobbes’ Leviathan—a ruler trusted with absolute authority in exchange for security. After decades in which fear dictated the boundaries of daily life, many Salvadorans eagerly accepted Bukele as their sovereign. For a society once governed by warring gangs, the concentration of power by a single figure felt less like a threat and more of a relief.

Barrera agreed, yet he warned that this stability is built on a grand illusion, “There is no peace if thousands are suffering in prisons, and there is no freedom if El Salvador is one of the countries with the highest incarceration rate in the world.” For him, the calm does not eliminate violence but enables it under the régimen de excepción—from the streets to the prisons, from the gangs to the state.

The régimen de excepción, declared in March 2022, suspended the constitutional rights that once limited state power in order to enable Bukele’s hardline anti-gang policies. Under the decree, police can arrest people without evidence, hold people without official charges, and prolong pre-trial detention. Habeas Corpus disappeared overnight. Trials are now rarely held, and if they are, they are almost always collective: trials with over a hundred defendants tried at the same time. With over 80,000 arrests, El Salvador has the highest incarceration rate in the world.

Prisoners’ accounts of incarceration are strikingly consistent: overcrowding, starvation, beatings, and systemic torture. Hundreds of detainees have died in captivity, with many families not knowing whether their relatives are alive—let alone where they are held. Dozens have simply disappeared.

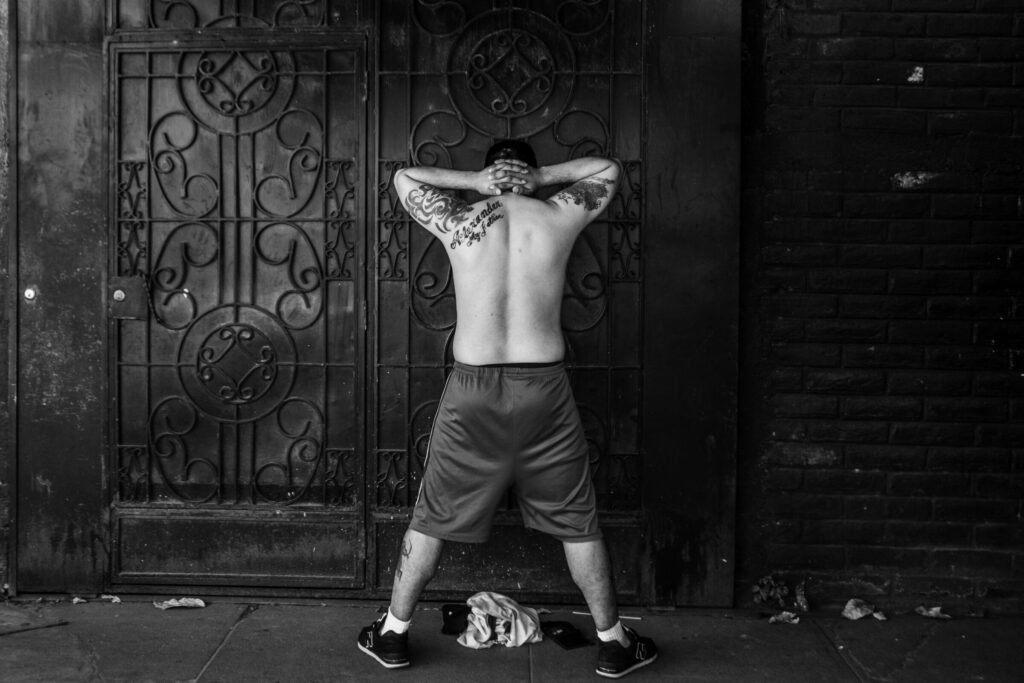

Barrera has reported consistently on the state of exception. “My main goal was to give a name and a face to those detained, those tortured, and those murdered.” One of the earliest photos he took captures this reality with brutal clarity: a shirtless man kneeling, surrounded by five soldiers, soon to be taken to jail. “The man is subdued; he can do nothing,” Barrera recalled. “He looks like prey that has surrendered and is about to be devoured.”

Still, for many Salvadorans, this violence coexists with another difficult truth. Perez told me she feels torn when she sees photos from the prisons. “These people were monsters when they were out of prison,” she said. “They raped people, they killed people, they had no concern for human life. I have no pity for them.” But even she draws a line, “It’s inhumane. I have no pity for them, but I do think it’s inhumane.”

What complicates this dichotomy further is that not everyone inside the prisons committed a crime. Thousands, like Jorge, have been arrested on false or flimsy accusations, detained simply for being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Perez’s words capture a tension felt across the country: relief at the disappearance of gangs, tempered by the growing awareness that the state’s newfound power may not stop at the prison gates.

Barrera sees this tension in external international perceptions of El Salvador, especially compared to internal perceptions of the state. “Many abroad think everyone arrested is a gang member, that the country is free,” he said. “In reality, it has the highest incarceration rate in the world and constant abuses of human rights.”

As the allegations of torture and deaths in custody become undeniable, more and more Salvadorans are approaching the regime with caution. Carlos Salamanca, director at Cristosal, a Central American human rights organization, echoed this change. “The state of exception, as a concept in general, is still popular, but not as popular as it used to be a year ago,” he said. “Because there are many reports now … about tortures, deaths in public custody, and corruption.”

***

Regardless, he warned, the core tenets of democracy are quietly crumbling away.

Nearly half the country is afraid to express an opinion about the government, according to Barrera. With courts neutralized, opposition parties disbanded, and public dissent shrinking, El Salvador now functions less like a democracy and more like a state governed by a permanent emergency.

The political culture of El Salvador has shifted as much as its political institutions. “There are no political parties left,” said Perez. “[Bukele] is very Machiavellian.”

No institution has felt the democratic collapse more than the press. Between 2020 and 2021, 22 El Faro journalists were spied on using Pegasus, a spyware system available only to governments. The outlet further faced weaponized audits and smear campaigns, Barrera added, aimed solely at discrediting its reputation. After El Faro published evidence of secret negotiations between Bukele and Barrio 18 in May 2025, seven arrest warrants were issued for their staff. Barrera and his colleagues fled the country and have spent the last six months living in exile across Central America. “This has radically changed the way journalism is done,” Barrera noted.

Salamanca and his colleagues at Cristosal are similarly located outside El Salvador. He told The Politic that after his colleague Ruth Lopez was arrested on false charges in May of this year, Cristosal realised the political environment was too hostile for them to survive in the country. “If Ruth, one of the most respected voices of human rights defenders, was detained…what would happen with us, who don’t have that kind of protection?” Salamanca added. “Organized civil society is either outside El Salvador or…operating more clandestinely in El Salvador.”

***

Even amid this landscape, small forms of resistance have begun to surface. The most visible is Movement of Victims of the Regime (MOVIR), a grassroots network of families whose relatives have been detained under the régimen de excepción. They have no office and no formal structure—just four coordinators, organized entirely by cell phone. Even so, they have been able to mount demonstrations demanding information about the disappeared. On her most recent visit, Dr. Montgomery saw the movement growing. “It’s mushrooming,” she said. “They don’t keep records, but I look at the pictures, and there are hundreds [of members].”

She sees MOVIR as the first seed of a fragmented opposition to Bukele. She recalled a saying from the 80s, “Salvadoreños son tan tercos como las mulas”––Salvadorans are as stubborn as mules. For her, it’s a reminder that civil society, no matter how battered, refuses to disappear.

Regardless, Bukele remains overwhelmingly popular. For many, the dismantling of Salvadoran gang violence trumps all other concerns. And yet, security without justice is meaningless. The human cost of his regime is impossible to ignore. The same policy that emancipated neighbourhoods from gang control has filled prisons with thousands of innocent people who were taken on suspicion, denied counsel, and held without trial. In prison, starvation, beatings, and torture are routine. Hundreds have died in custody: Alexander Guzmán, who survived six months of starvation and abuse; Marco Tulio, beaten so badly he bled to death; Jorge Amaya, a student who has still not come home. For every Salvadoran that sleeps restfully, another awakes to a nightmare. “It would be logically contradictory to consider it a free and peaceful country,” Barrera reflects.

Salamanca is worried about the future. “The structural conditions that generated gangs have not been addressed at all,” he said. “Eventually when the régimen de excepción finishes, I think there will be some kind of mutation.” From young kids with parents incarcerated to widespread youth unemployment, he is afraid that gangs may begin to regenerate. “There’s a lot of anger with young people,” he added.