At 8:30 a.m. one mid-October morning, Oumar Konipo arrived at a gas station in Bamako, Mali. For the 73-year-old retired United States Embassy worker, who has lived in the city since 1968, this was a familiar errand. Konipo waited until 2:30 p.m. to finally fill his tank. For Konipo, who is active and in good health, the wait was bearable. He explained, however, that “there are many people my age who cannot… [spend] five, six hours just to get 20 liters of gas into [their] car.”

Piles of vehicles surround fuel stations, spilling into the streets. This is the new reality for the five million people living in Bamako, Mali’s capital and largest city. The shortages are the result of a nearly three-month fuel blockade by the Al-Qaeda-linked militant group Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM).

By choking off fuel imports from Senegal and the Ivory Coast—lifelines for the landlocked nation—the blockade has put immense pressure on Bamako’s residents. “People are encouraged to take their old bicycles out,” described Konipo. “You cannot get to your job if you don’t have gas to put in your car.” In light of transportation issues, the military government, led by President Assimi Goïta, closed schools for two weeks. In October, the U.S., the U.K., and France ordered evacuations of their citizens from the country.

Fuel shortages have led to power outages, and most economic activity has become dependent on small electricity generators. “If you don’t have gas for the generators, [or] if the electric company does not have gas for its big generators, then it [creates] a lot of problems,” said Konipo.

This is “the first time we’ve seen [Mali’s] economy completely under siege,” explained Beverly Ochieng, a senior analyst at the risk management consultancy Control Risks.

“Goods coming to Bamako–– rice, architectural products, or cotton harvests––cannot reach the factories,” explained Konipo. “A small company that cleans clothes does not have electricity to do its job. The grinding mill in the neighborhood that should have flour is not working. Such are the constants of daily life in Bamako today.” In the standstill, people like Konipo await an uncertain future.

***

Mali is a country with a history of resilience in the face of uncertainty. Over the past two decades, waves of military coups, terrorist activity, and insurgencies have gripped the country. With them has come the familiar public grievances and humanitarian challenges of security, economic, and political instability. Though these challenges have remained the same across time, what has changed is the degree of international support and attention in Mali. The choking of Bamako represents the consequences of this decline.

Mary Beth Leonard was the U.S. ambassador to Mali from 2011 to 2014 when a rebellion of ethnic Tuareg groups, a military coup, and the rise of jihadists in the North plunged the country into instability in 2012. For her, it was primarily important to support Mali’s return to democratic governance “as quickly as possible,” as democracy was conditional for U.S. support. Following the appointment of an interim civilian government in 2013, she described how the international community came together to address the crisis. Support came from the UN peacekeeping mission MINUSMA, the Economic Alliance of Sahel States (ECOWAS), and the French Operation Serval, to protect civilians from jihadist groups and prevent the spread of terrorism across the broader Sahel region.

The U.S. had been an important strategic partner for Mali. “While I was at the embassy, the U.S. spent a lot of money training the military,” said Konipo. “The officers received excellent training, and I witnessed that myself.” He noted, however, that despite all the training and money, the terrorist activities kept growing. For some, there was a growing sense that Western intervention was not sufficient to halt the violence.

“It was a period of great emotion,” described Ambassador Leonard, “I don’t think that that emotive temperature has necessarily ever gone away.” In a reflection of the military’s deep grievances over its authority during this period, the current military junta overthrew the civilian government in 2020.

Konipo worked at the U.S. embassy as an economic and political specialist. “I traveled the entire country with seven different ambassadors, from west to east, north to south… my role was to help both sides understand each other: to make sure our American officers understood Malian culture, and that Malians felt respected and heard.” Today, a concerted effort of cultural diplomacy and dialogue, and sustained attention of Mali by the international community to support a political solution, has been lost.

In 2015, an American NGO known as The Carter Center was appointed as the independent observer of the Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation, an agreement that marked the end of three years of fighting between Tuareg groups and the government. It was the first time an independent observer had been written into an African peace agreement. Bisa Williams, former ambassador to Niger who led the Carter Center’s efforts, said “I did not feel that the right kind of sustained attention was being brought to the process,” adding that there was “no accountability, no enforcement. I found that extremely frustrating.”

Similarly, MINUSMA was initially successful in supporting the protection of civilians and stabilizing urban centers. It would also become the deadliest peacekeeping mission in the world. The mission operated in a highly volatile security environment, and it was inadequately resourced to carry out the extent of its mandate effectively. At the crux of these challenges was the breakdown of the relationship between the peacekeeping mission and Mali’s government, as it has shifted its partnerships and level of cooperation over the past decade.

In early 2022, the government led by President Goïta completely severed its ties with France. In the same year, the military junta invited the mercenary Russian Wagner Group, a group of armed mercenaries, to replace the French in managing the terrorist threat. In 2023, the military government ordered the removal of MINUSMA peacekeeping forces.

After leaving ECOWAS that same year, Mali formed the Alliance of Sahel States with the military governments of Niger and Burkina Faso. This alliance reinforced the dramatic reorientation of these states away from democracy and Western support. In 2024, the Malian government ended the Agreement for Peace and Reconciliation. The Alliance of Sahel States then withdrew from the International Criminal Court, citing “neo-colonial repression.” Traditional mechanisms of international accountability and enforcement are no longer in place.

“This country decided to get together to…stand against countries, including Western countries…not helping them, [not] respecting the country…and considered as not supporting the sovereignty of our country,” described Konipo. “So that’s what many people see, and in good faith, when they believe that colonial countries like France are still in our countries to exploit us.”

***

There are inherent frictions between the anti-colonial politics of the military government and the lived reality of the Malian people. The military junta has struggled to maintain security amid expanding insurgent activity since coming into power. In 2024, Mali ranked fourth in the world on the Global Terrorism Index. The military has proven ineffective in ensuring consistent security and providing basic state services for rural populations. Most importantly, the government has failed to establish effective governance in a way that prevents terrorists from regrouping.

In the past, JNIM did not have the numbers to enforce a blockade of Bamako at the present scale. “But they have been actively moving their militants to reinforce their ranks and coalesce their concerns across the region,” Ochieng explained. Now, she said, “what they’re pushing for is economic paralysis.” JNIM aims to weaken the government by escalating public grievances over the collapse of basic services. The subsequent economic and political pressure is likely intended to force regime change or extract leverage for a power-sharing deal with the government.

The current fuel blockade in Bamako stems from a strategy employed by JNIM across the country. “In central Mali,” Ochieng explains, “they would blockade farming areas, burn their farms, [and] seize livestock en masse.” Many local agricultural communities are left with no choice but to transact with jihadists or face coercion and extortion. JNIM has stripped the region of its economic autonomy.

Areas in North Mali are controlled by several armed Tuareg and Islamist groups, in addition to JNIM. By controlling artisanal gold mines, these groups operate in a shadow economy that funds and resources their operations. JNIM strengthens its de facto authority in the region by recruiting local informants. As Ochieng explains, “JNIM is really good at embedding itself in local communities and co-opting sentiment and grievances.”

Government counterterrorism is often coercive and violent, frequently resulting in indiscriminate reprisal killings. In a recent example, in Diafarabe, a town in central Mali, the military reportedly rounded up between 23 and 27 men and executed them extrajudicially. There are also cases of civilian casualties, such as the massacre in March 2022, where the military killed over 500 civilians in central Mali.

Through this repressive strategy, the military has perpetuated a cycle of violence. As Franklin Nossiter, a Sahel analyst at the International Crisis Group described, “we have been saying for years that [terrorism in Mali] is not something that you can deal with by [using] a purely military solution. You need a negotiated solution. You need a political solution. You need to talk to these groups.”

In areas where the military does have effective control, the junta has blurred the line between the military’s role in defending the country and political leadership. “The military is everywhere now,” says Konipo, “in civilian positions, ministries, even directing hospitals and energy agencies. That’s not their job.” He notes that today, people do not join the military to fight, but because “you are likely to someday be a chief, a minister, [or] president. It’s very sad.”

In July, the military-appointed legislature extended President Goïta’s term by five years—renewable indefinitely without elections—following his seizure of power in a second coup in 2021. Military authorities have since dissolved all political parties due to political fragmentation.

Military control extends to the media and judicial system as well. “Newspapers that are aligned with the government say things that do not have any proof,” says Konipo. “People do not believe in judges anymore because a judge cannot make a decision they want. They make the decision that they are asked to make.”

For Konipo, President Goïta’s military government is inherently fragile because it is wildly undemocratic. “Today, [open] communication is an issue. Corruption is an issue. People do not have confidence in their leaders, in their neighborhoods, and feel afraid of saying things that may lead them to go to jail. That’s the system.”

***

Mali was once an epicenter of international cooperation. Now, given the fuel blockade, Mali has been abandoned, as a result of weakening international interest and investment, and the deliberate realignments of the military government. This trend has broadened across the Sahel, where military governments now rule in Niger and Burkina Faso.

“In the past, the U.S. could lean on the French, the AU [African Union], ECOWAS, and we helped subsidize their troops. That’s gone now,” said Harry Thomas, former U.S diplomat and leader at Special Operations Command.“Without U.S. leadership, [the region] just becomes a vacuum.”

Should the present blockade lead to negotiations between the government and JNIM, and a power-sharing agreement fails, the regime would collapse without an immediate successor. Ochieng suspected a chaotic situation where “there’s no clarity on who is leading Mali, and [there is a] prolonged siege and infighting by militant groups and potential war.” When democracy and international institutions collapse into anarchy, people will suffer.

“For me, the jury is still out for Mali—on how seriously it will take this notion of forging a true Malian Republic where [Mali] can engage with the rest of the international community,” said Ambassador Williams.

***

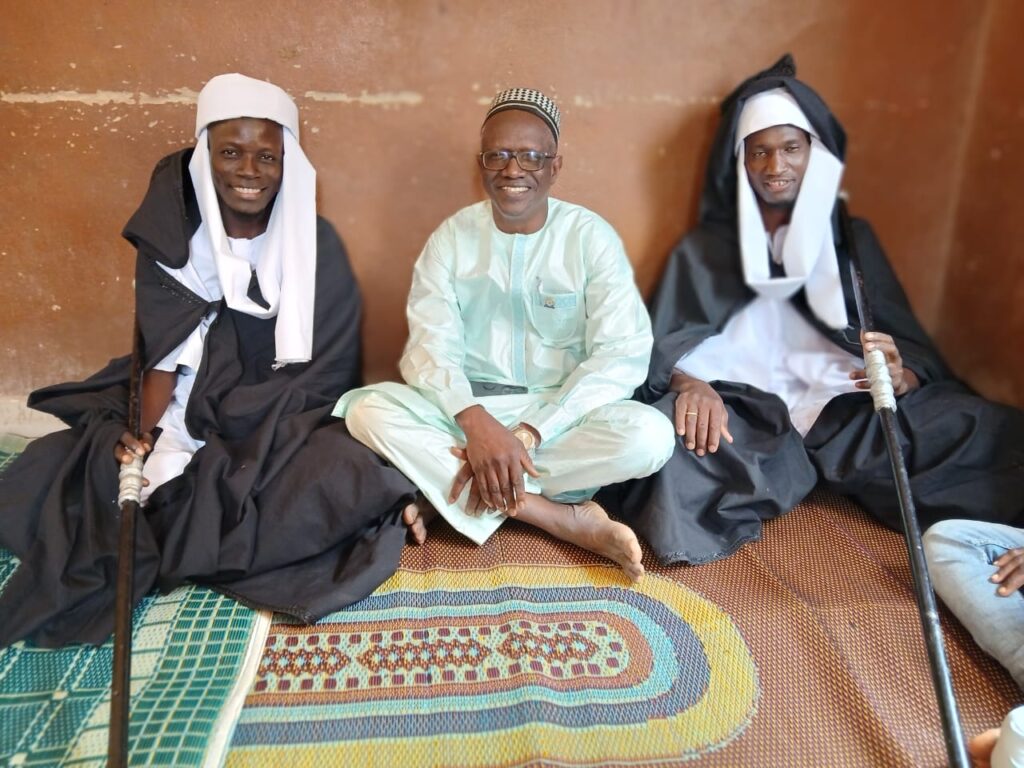

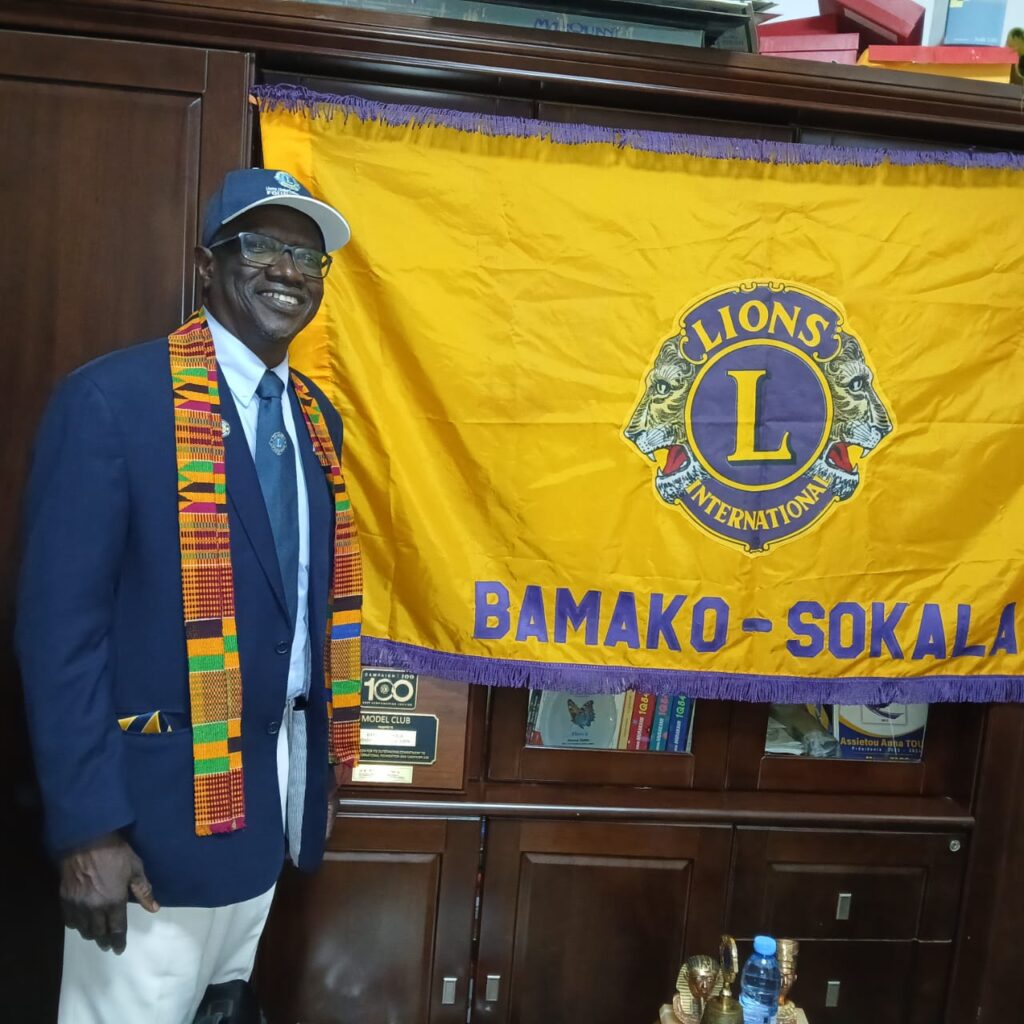

Despite Bamako’s sprawling fuel lines, Oumar Konipo remains committed to public service. Since 1999, he has been involved in Lions Clubs International, the world’s largest service organization. His club digs wells for village communities, supporting school children and women’s cooperatives. “It’s a lot of sacrifice, but I love it. I am now the second vice governor for eight countries, including Mali, Senegal, and Mauritania.”

Konipo navigates his humanitarian work through communication and inclusion, just as he did during his twenty-five years at the U.S. embassy. On each project he takes care to explain to all stakeholders––from the military governor, the chief, local associations, and women’s groups––what he does and asks for their help. He wants everyone to contribute because “when we work together, we are the same people.”

Konipo sees a path forward for Mali in embracing this spirit. He stresses the importance of a strong civil society: local associations, not political groups, that speak to their community’s needs and defend their rights. “I’m confident that we’ll get out of this,” Konipo concluded.

Above all, Konipo places his faith in the youth, and in preparing them to build the future. When raising his own children, he told them: “you should give back to your country more than you got from it.”